Between 1946 and 1949, a mass post-war immigration drive sought to repatriate Armenians to Soviet Armenia. Around 90,000 took up the offer; they were families that had been displaced from their homes in the former Ottoman Empire during the Armenian Genocide. Some may have been partial to socialism, but most of those boarding the ships in Beirut were looking for a place where they belonged, an Armenian homeland, even if it was no longer independent. The historical event was known simply as the Nergakht (The Immigration).

Upon arrival, the situation they faced fell short of their dreams. They were viewed with suspicion as outsiders to the communist system. In 1949, the deportations began.

* * *

“Almost all the Armenians of Tbilisi—and there were more Armenians than Georgians in Tbilisi—had gathered not far from our parking lot. Everyone was shouting, crying, looking for their relative, brother, sister, mother, wife, bride, acquaintance. Men and women, old men and children alike were crying. I had never cried like that in my life… And how could you not cry when unexpectedly, in an hour, so many peaceful residents were being exiled from the city.”

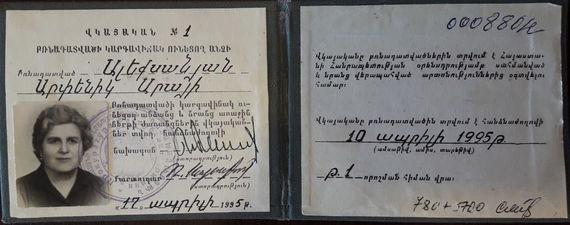

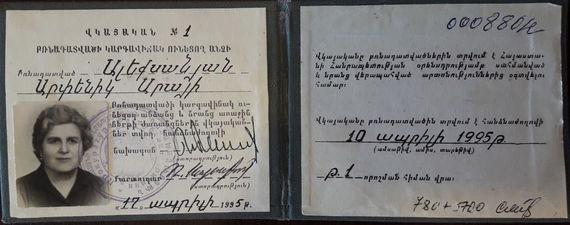

-Arpenik Aleksanyan, (Siberian Diary: 1949-1954)

* * *

On July 8, 1949, Konstantin Bziava, the Minister of Internal Affairs of the Georgian SSR, wrote a report to Vasily Ryasno, the Deputy Minister of Internal Affairs of the USSR:

July 8, 1949

Top secret

N 1/00479:

The operation of receiving the special contingent and sending them by echelons was completed on June 18 of this year. The preparatory work was carried out in an orderly and organized manner. 76 officers took part in the operation. No violations of public order, anti-Soviet or other manifestations were reported during the operation.

A number of technical inaccuracies were recorded during the operation. Due to the uncertainty of defining and registering the contingent, their number was more than had been planned for, requiring an additional 5 echelons.

At the request of the State Security of the Georgian SSR, more than a 100 people were removed from the contingent and sent back on June 17 and 18. Due to the unplanned dispatch of the contingent, there were crowds at the reception points of Eshera and Kelasuri in the Abkhazian SSR.

A total of 25 echelons have been sent.

In total, 8,143 families (36,451 people) were sent from the Georgian SSR, including Turks – 762 families (2,500 people); Greeks – 6,692 families (31,274 people); former ARF families – 689 families (2,777 people).

One of the 689 families mentioned in the report was that of Arpenik Aleksanyan. Her father was not a “former ARF member”, but in the 1910s he moved from Turkey to Russia in search of employment. In the mid-1920s, he received Soviet citizenship. But the authorities were not interested in facts; in 1949, he was exiled to Siberia, together with his family.

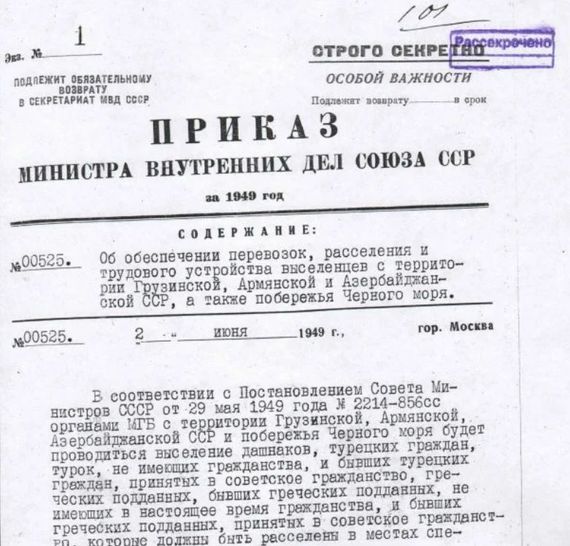

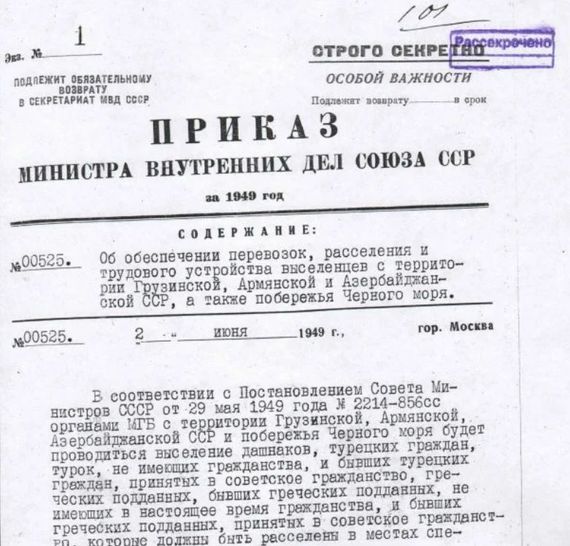

On the night of June 14, 1949, tens of thousands of people in Armenia, Georgia, Azerbaijan and other Soviet republics, including many Armenians, were loaded on freight trains at about the same time and sent into the unknown. At the heart of this great tragedy of deprivation and human destiny was Order No. 00525 of the USSR Ministry of Internal Affairs, dated June 2, 1949, and bearing the “Special Importance” and “Top Secret” classifications.

It read: “According to Order No. 2214-856ss of the USSR Council of Ministers dated May 29, 1949, Dashnaks, Turkish citizens, stateless Turks, former citizens of Turkey with Soviet citizenship, and former Greek citizens who now have Soviet citizenship will be exiled for life from the territory of Georgia, Azerbaijan, Armenia and the coastal regions of the Black Sea.”

Order No. 00525 defined the areas to which the exiles were to be transferred:

In order to implement the decision of the USSR Council of Ministers accurately and on time, I am ordering deportees from the Georgian, Azerbaijani, Armenian, Ukrainian SSRs, Krasnodar Territory and Crimea region to be exiled and resettled for life:

Dashnaks to the Altay Territory – 3,620 families (13,000 people)

Turks to the Tomsk region – 1,500 families (5,400 people)

Greeks to the Jambul region – 6,000 families (21,600 people)

Greeks to the South-Kazakh region – 1,500 families (5,400 people)

-USSR Minister of Internal Affairs, Colonel-General S. Kruglov

Order No. 00525

Abram Kisibekyan

Abram Kisibekyan, who was a teacher, writes that they also tried to send him and his wife to work on a collective farm, but they resolutely refused. “The next day, the director came… He suggested we go and work in the state farm’s fields or tractor stations. Five of us refused. One morning, the commandant came and ordered us to go to the field as well; we refused. The commandant suggested I work as a night guard, but I refused,” writes Kisibekyan.

Shakhov also noted that among those who refused to work on collective farms were many “people who had come from abroad,” referring to repatriates. The latter, according to the report, “are obviously dissatisfied with the move to Siberia and are dissatisfied with the actions of the party and the government, slandering the political system of the USSR.”

There was also a reference to the living conditions of the settlers, some of whom—113 families—had not been able to find a suitable home and were living in tents, which could be fatal in the harsh climate of the Altay Territory.

“One day the leaders of the Tomsk Ministry of Internal Affairs appeared. They gathered everyone. The colonel stood on a mound and began to talk about us. He talked of our misfortune, ‘According to the Decree of the Presidency of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR of November 25, 1948, you are exiled for life, without the right to leave the Parbigski district of the Tomsk region.’ The colonel read various decrees and then said that, if anyone escapes after hearing all this, they will receive 25 years imprisonment. And if they give refuge to a fugitive, they will receive 5 years,” writes Arpenik Aleksanyan.

In exile, special settlers were hired for low-paying and menial jobs. They were also included less in public and political life. The relations between the local population and the special settlers were also unregulated, and there were often serious conflicts. This was especially typical of the Kazakh SSR, where the settlers from the North Caucasus and Transcaucasia were concentrated. In July 1949, a fight broke out between locals and resettled Greeks in the Kirov district of the South Kazakh region, in which 200 people took part; three Greeks were killed and many were wounded. In another fight in the town of Leninogorsk in the Eastern-Kazakh region, 34 Chechen settlers were killed.

Many of the children of special settlers did not go to school. As of 1950, 91,943 children did not attend school due to a lack of winter clothes and shoes, the poor financial situation of parents, and a lack of schools in some regions.

Arpenik Aleksanyan, 24 July 1951.

Reason for Exile

Scholars still express different viewpoints in trying to explain the purpose of the 1949 exile. Some consider it to have been based on national security considerations amid the possibility of conflict against the West. Others view it as an economic initiative for developing the remote regions of the USSR.

Historian Zohrab Gevorgyan thinks that the roots of the exile of the late 1940s lie in the period of collectivization: “Collectivization or deprivation of private property was not just an economic phenomenon, but an intention to transform the management of state resources into a pyramid structure. Collectivization first of all affected a person’s independent thought because, when you change the economic management system and deprive a person of private property, you also deal a very severe blow to his way of thought and worldview. By losing his private property, a person loses his independence. The 1949 exile was a continuation of the same process; it simply included other strata after the war.”

Considering the economic reasons for the exile in the late 1940s, Gayane Shagoyan, a cultural anthropologist and researcher at the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography of the National Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Armenia, notes that resettlement was used as a means to secure cheap labor: “The state was solving the issue of modernizing the economy. This was not so much a political as an economic issue. It is another matter, as to how productive it was to use people who could be useful in different spheres as blue-collar workers.” Shagoyan goes on to note that a number of Eastern European states were able to achieve economic development without using the tactics of exile and resettlement employed by the USSR.

The professional abilities of the displaced were almost disregarded; the vast majority were employed in the collective farms, and in forests as lumberjacks. “The professions of the people being resettled were not specified at all, except for the ‘sharashkas’, which were specialized closed institutions [secret R&D labs]. For example, the arrested or resettled physicists who worked on projects to create a nuclear bomb,” said Gayane Shagoyan. She mentions that, although there were also other resettlements from Armenia and other republics of the USSR, the one in 1949 was the largest. During the war, a large number of people were deported on ethnic grounds—the Kalmyks, Chechens, Ingush, Kabardians and others.

“Both before and after the war, social groups that were perceived as disloyal to the government were being moved from border zones into far flung regions of the country. In the case of the exile of Armenians, two accusations were usually presented; one was cooperation with Nazi Germany, which was formulated as a ‘participant-member of the Armenian Legion’. However, the resettlement lists included those who had simply been taken prisoner, regardless of whether they were in the Legion or not. The second large group were the Armenians who had had other citizenships. In the case of Armenians, it was very unfair, because people who had had to flee the Ottoman Empire because of the Genocide were exiled to Siberia on charges of being citizens of the former Ottoman Empire,” said Gayane Shagoyan.

As for those who repatriated in 1946-1948, according to Gayane Shagoyan, they made up 10-12% of the total deportees from Armenia.

Arpenik Aleksanyan’s diary, which was published in 2007 under the title “Siberian Diary” is the most remarkable testimony of the 1949 exile. The book is also extremely valuable because it is Arpenik’s daily record; thus it contains direct and reliable information about the resettlement—starting with leaving her home and ending with her return in 1954.

“My mother was studying at the medical university. She had passed four out of seven final state exams and was going to become a certified doctor. She was an Armenian girl from Tbilisi who bore the culture of that time. Everyone in exile knew that Arpenik was keeping a diary, but they did not inform anyone. Nor did they hand it over to the authorities. They understood that there was someone who was recording their lives, the lives of those in exile,” recounts Arpenik Aleksanyan’s son, Harutyun Marutyan, who is now the Director of the Armenian Genocide Museum-Institute.

“In exile, they tried to recruit my mother. They even threatened her at gunpoint, but she refused to cooperate. She remembered that episode until the end of her days. Instead of fairy tales, she told my sister and me stories of Siberia,” says Marutyan.

Despite all the tragedy and difficulties of exile, there is still humor and endless optimism in Arpenik Aleksanyan’s book. Even in the harsh conditions of Siberia, young girls were trying to live, to be happy and were confident that, one day, the misfortune would come to an end.

Arpenik, her mother and younger sister, 1952.